Much is said about the prominent place of Indian-Americans in US society. Sporting a range of leaders in business, medicine, sciences, and the arts, and boasting the highest per capita income among ethnic migrant groups in the US, the community is an incarnation of the American dream. Brown people have officially moved from the “arrived in America with eight dollars” refrain into medical scrubs on television shows, and have bespectacled math whiz children. The community is very visible – especially in suburbs with well-rated public schools. Around mid-August each year, a series of floats featuring choreographed Bollywood dances in front of Styrofoam Taj Mahals laze through American cities to the loud beat of Bhangra, shorn of Khalistani innuendo.

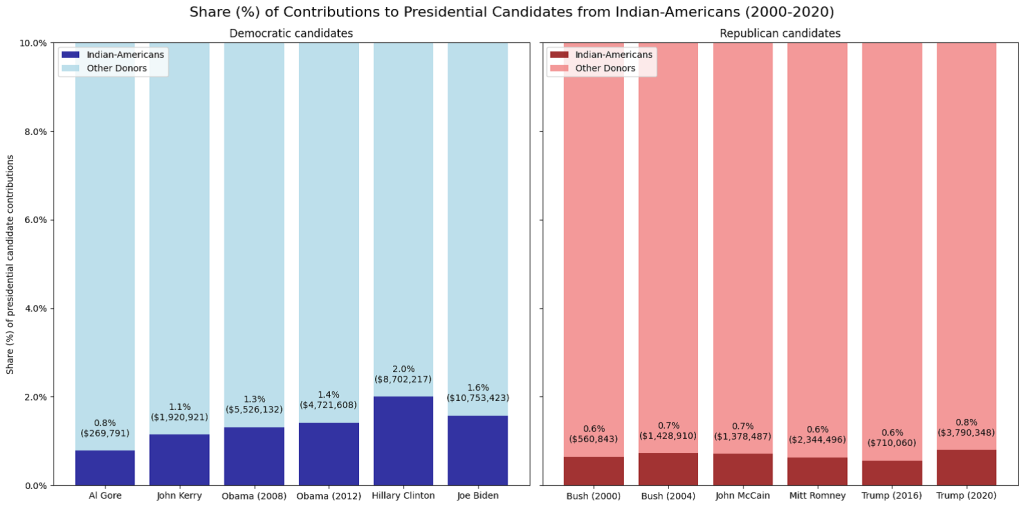

No Republican candidate has ever received a lower share of presidential funding from Indian-Americans than Trump – in both the Clinton and Biden campaigns.

In the last two decades, Indian-Americans have also entered and evolved in national politics, starting with the ‘American-sounding’ Bobby Jindal and Nikki Haley, to the unapologetic owners of names like Vivek Ramaswamy and Suhas Subramanyam. By the 2024 election, Indian-Americans had a presidential candidate and six seats in the US House of Representatives. But outside of the names, little is known about the political footprint of this very visible community, which now accounts for about 2% of the US population.

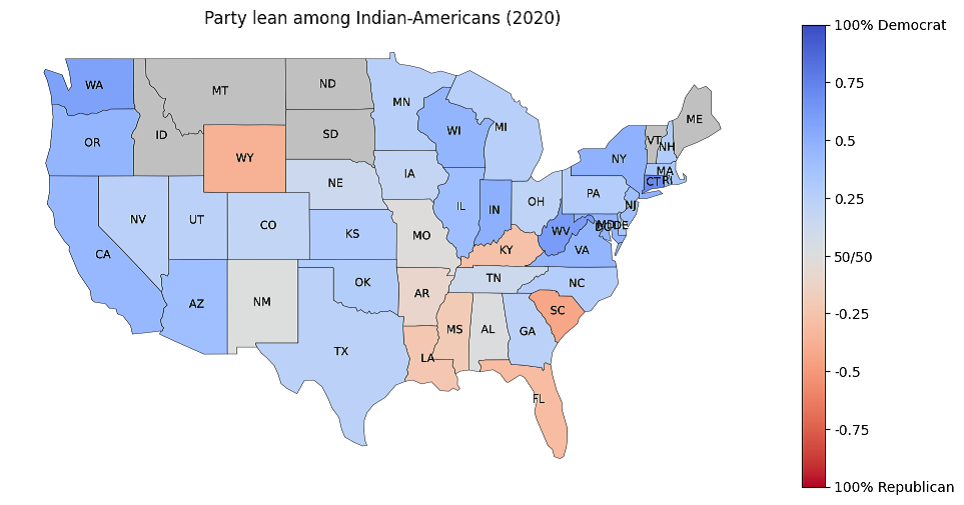

Figure 1: State-wise map of the ratio of contributions from Indian-Americans towards Democrats versus Republicans. 1 (dark blue) indicates 100% of contributions went to Democrat candidates and committees, while -1 (dark red) indicates 100% to Republicans. States with less than $100k in Indian-American contributions are in grey. Source raw data: Opensecrets Campaign Finance Data

And yet, Indian-Americans had served as a diplomatic back channel for repairing relations between the two countries. Since the end of the sanctions regime which followed India’s 1998 nuclear tests, the relationship had been uniformly good. But suddenly, the tariff war and the Trump government’s sustained assault on H-1B visas dramatically changed perceptions of Indian-Americans’ influence on US foreign policy towards India. The Indian media reflected a sense of betrayal. The successful Indian-American, for long the hallmark of middle-class aspiration, had over the last decade aligned slowly with India’s right. Trump had once, briefly, followed Modi on Twitter. Modi had once held his hand. Ties between Modi and his NRI friends, which brought technology firms and networks to the homeland, became top-shelf television.

Then one day, Indian viewers were delighted to find that Modi’s arm-candy at the ‘Howdy Modi’ event in Houston was the second-most powerful man in the world, Trump himself. For a moment there, the cheers of “Ab ki Baar Trump Sarkar” (“This time, a Trump government”) sounded like an anthem for elites of both nations to sing in unison. But Trump lost. And by the time he won again, he wasn’t quite ready to hold hands with his old friend again.

Indian-Americans do one thing which most immigrants in the US do: they vote Democrat. Till 2022, they were among the most Democrat-leaning of all migrant ethnic groups. And as if that weren’t enough to annoy Trump, it’s also where Indian-American money goes.

So what went wrong? Did our NRI friends fail us? Was campaign funding an issue? With Trump back in power, air-conditioned Indian WhatsApp gloated over the demise of wokeism, screaming paeans to our orange friend. The dominant discourse on the Indian news was that Indian-Americans largely leaned right. Believers in meritocracy, they had been cheated by India’s welfarism in education and state employment, so anti-wokeism, which pushed back against the inclusive workplace, seemed perfectly aligned with the desi ethic. Their Silicon Valley aura radiated libertarian exceptionalism, elevating them above immigrants from what Trump had called the “shithole countries”. But Figure 2 reveals data illustrating Trump’s disenchantment with India. No Republican candidate has ever received a lower share of presidential funding from Indian-Americans than Trump – in both the Clinton and Biden campaigns.

Figure 2: Election-wise distribution of presidential candidate funding by Indian-Americans, showing that Trump received the lowest share of funding compared to his Democrat opponent. Source raw data: OpenSecrets Campaign Finance Data.

While desi pride about being valuable additions to American society who came to the US the hard way and worked their way up persists, something else has been rubbing Vicco Turmeric onto our ironed kurtas of model minority pride. It turns out there are other Indians, too – they’re the third most numerous group crossing the Mexican border to join millions of undocumented migrants in the US. Like Central Americans, Indians found themselves being chained and deported.

And there’s yet another way in which we resemble the immigrants we avoid allying with. Indian-Americans do one thing which most immigrants in the US do: they vote Democrat. Till 2022, they were among the most Democrat-leaning of all migrant ethnic groups. And as if that weren’t enough to annoy Trump, it’s also where Indian-American money goes. It turns out that Indian-Americans have overwhelmingly supported the Democrat party and funded its candidates from 2000 to 2022. And just about every professional category of Indian-Americans is more likely to fund Democrats than Republicans.

All of the six Indian-Americans in Congress are Democrats, representing districts which have at least two of these three characteristics: (1) they are wealthier than the average American House seat, (2) they have a high share of immigrants, and (3) they are safe Democrat seats. The overlap between Indian-Americans and other immigrants on political issues matters significantly because it is not clear if an immigrant who happens to be a person of color can actually win an election as a Republican in most of the US, especially if they retain their birth faith. Two Republican Asian Americans, Young Kim and Vince Fong, have won elections from immigrant-heavy districts, but both are Christian, and one Arab American Republican from Arizona, Abe Hamadeh, while born Muslim, self-identifies as ‘religiously non-affiliated’. The only two Indian-Americans appointed to major office on the Republican side – Bobby Jindal and Nikki Haley – are converts to Christianity. Contrarian candidates like Vivek Ramaswamy have more performative value as Republicans who do not fit the White conservative stereotype, rather than as serious candidates.

In other words, it makes sense for Indian-Americans to caucus closely with Democrats, and our research clearly shows that this has been historically true. And despite the talk of Modi putting his weight behind the American right, when we follow the money, it moves in a progressive direction. Our new report into two decades of funding towards US elections by Indian-Americans shows that the community has had a relatively slow but deliberate and growing effect in the bloodstream of American politics. In the early 2000s, there was talk of building organized political lobbying by Indian-Americans through USINPAC, like the Israeli lobby AIPAC. But unlike AIPAC, which has been far more successful in creating coalitions with politicians across the country, the separation from the Judeo-Christian block has been an impediment to getting Indian-Americans or India to be part of the conversation in most of the deep Republican seats. In the mid-2000s, after the US banned Modi from securing a visa, there was a slow but organized move to getting more India-specific traction among evangelical lawmakers from middle America, which is now more or less a thing of the past.

The report shows that the flow of funding towards Democrats has in fact increased between 2000 and 2022, to a point where roughly two-thirds of Indian-American funding went to Democrats. (The 2024 data may show a change.) More importantly, the culture of funding politics has grown among Indian-Americans – 1.3% of them were donating by 2022, up from just 0.6%. While our method of tracing this can lead to under-counting, it nonetheless suggests that Indian-Americans are much less likely to contribute to political elections than Americans of other ethnic backgrounds. This may be partly attributed to the political donation culture in India, which tends to be extortionist, and is not driven by citizens proactively supporting their preferred parties. During Indian elections, the citizen expects the politician to pay them a wad of cash, not the other way around.

The report shows that the flow of funding towards Democrats has in fact increased between 2000 and 2022, to a point where roughly two-thirds of Indian-American funding went to Democrats.

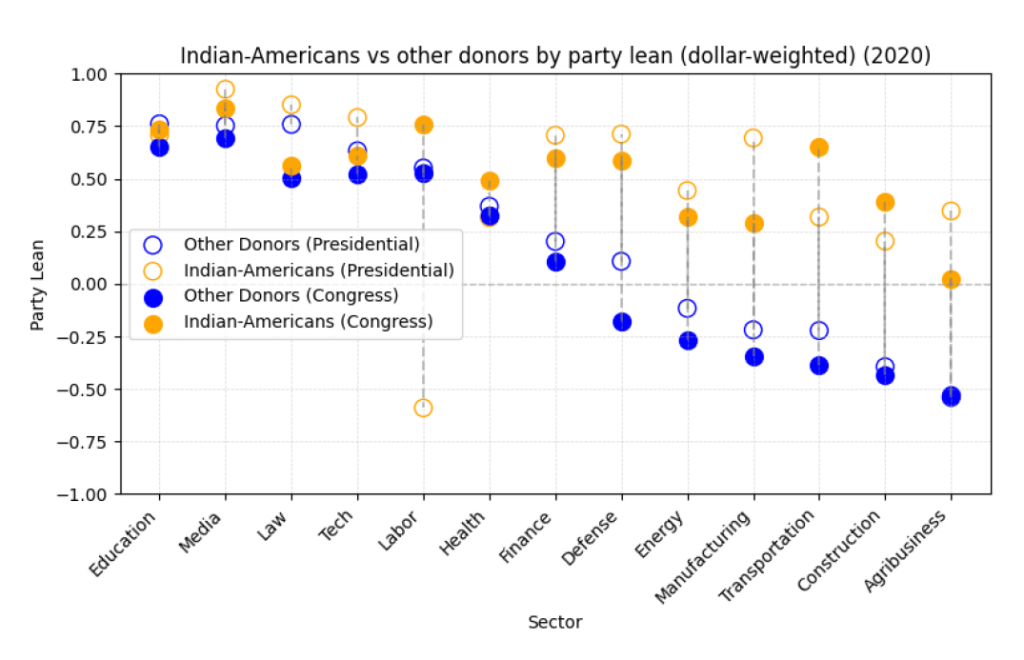

We also found that a small number of states with higher proportions of Indian-Americans – California, New York, Texas, New Jersey, Illinois and Washington – dominate the political donation landscape. The donations do not come from working class Indian-Americans. Instead, the most significant proportion comes from technology executives, healthcare entrepreneurs and financial sector figures. In terms of headcount, more people in the medical profession donate to elections, but in terms of the quantum of money, finance leads. We see here that in almost every sector, with the slight exception of tech, Indian-Americans lean more Democrat than Republican in their funding behavior.

Figure 3: Party funding polarization among Indian-Americans by sector. Source raw data: OpenSecrets Campaign Finance Data.

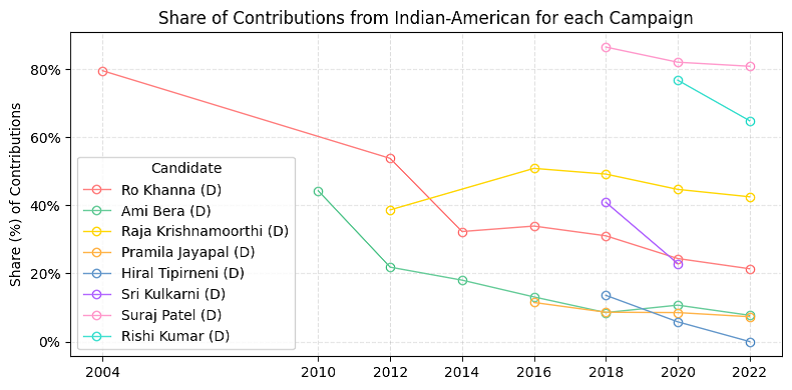

The Indian-American community kickstarts its candidates’ careers. Indian-American political candidates get a large share of their initial seed funding from within the community and over time, the contribution of the broader constituency increases. Ro Khanna and Suraj Patel, both from South Asian-heavy constituencies in the San Francisco Bay area and New York City respectively, received about 80% of their first campaign funds from others within the community. In Khanna’s case, the proportion had dropped to the 20% range, suggesting a solid mainstreaming.

Figure 4: Share of Indian-American funds in key candidates’ funding. Source raw data: OpenSecrets Campaign Finance Data.

Only two candidates from among Indian-Americans have consistently stood for and won elections from constituencies in which Indian-Americans do not form a significant share of the voting population – Pramila Jayapal in Seattle and Shri Thanedar in Detroit. Both, however, are in safe Democrat seats. Jayapal wins by virtue of being a progressive favorite in the Seattle area, whereas Thanedar outspends his competitors in the primaries by orders of magnitude, using his own millions.

The two Indian-American industry lobby groups that have the longest history of engagement with political funding – the American Association of Physicians of Indian Origin (AAPIO) and the hoteliers’ lobby Asian American Hotel Owners Association (AAHOA) are both still in play, but the level of coordination and organization across groups under a single ‘Indian-American’ umbrella is still extremely limited, outside of minor seed funding for candidates.

Overall, we see that the Indian-American strategy is not monolithic. While there are very few mega-donors from the community who can directly impact the outcome of elections, there are increasingly fundraisers, especially on the Democrat side, who are well connected in the community and able to move funding. The data from 2024 may bring up a few surprises, but on the whole, Indian-Americans are a solid Democrat-leaning community, irrespective of the belief that homeland politics are an indicator of leaning here in the US. As for the popular notion in India, that Indian-Americans dominate public life in the US, or that Modi is a widely regarded leader among US politicians, the reality of what is unfolding says more about it than any data needs to.

Are You Passionate About India's Future? Join Our Community to Collaborate, Advocate, and Create Positive Change.